The Historical Context of Jesus. & New Testament (Romans)

LESSON FOCUS

In today’s lesson we will outline the history of the ‘intertestamental period’ (i.e. the period between the OT and NT) the Roman takeover of Palestine in 63 BC, and then to the fall of Jerusalem in AD 70, drawing attention to particular significant events

THE ROMANS

The republic of Rome had been growing increasingly powerful in the Mediterranean world for two centuries, and the first century BC saw its formidable armies under their powerful leaders (the most famous being Pompey, Julius Caesar, Anthony and Octavian, later called Augustus when he was emperor), taking over what had once been Alexander the Great’s empire – from Turkey, into Syria and to Egypt.

In 63 BC Pompey entered Jerusalem, including the Holy of Holies (the central section in the Jerusalem temple). This caused offence, but Pompey had no anti-Jewish agenda, and the immediate impact of the arrival of Rome was not huge, since Hyrcanus 2 – one of Alexandra’s squabbling sons – was given authority to rule in Jerusalem under the Romans.

THE HEROD FAMILY

The famous family to come to prominence under the Romans was that of Antipater, father of the man known to us as Herod the Great. Antipater was a cunning politician (from an Idumean or Edomite family, the Idumeans having been conquered and forced to accept Judaism during the Hasmoneans). He had supported Hyrcanus in his quarrel with his brother, and soon managed to ingratiate himself with the Romans, notably by giving military aid to the Roman leader Julius Caesar, when he was in a dangerous situation in Egypt. He was rewarded by being made governor of Judea and later by the granting of particular privileges in the Roman empire to the Jews (e.g. they were exempted from regular military service, and were allowed to meet for worship).

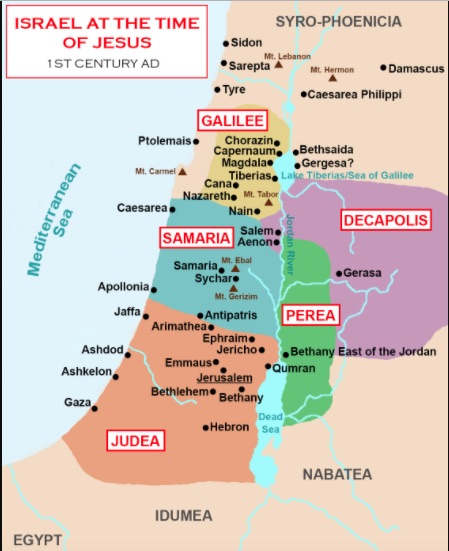

Neither Antipater nor Julius Caesar lasted long, both being assassinated. But Antipater’s younger son, Herod, in the face of considerable opposition, established himself in the favour of the Romans, and with their help fought his way into Jerusalem and into power. His ruthless campaign ended in 37 BC with a three-month siege of Jerusalem. From then on until his death in 4 BC, he was supreme in Jerusalem, king of all Judea, Samaria and Galilee.

Two Characteristics are notable about Herod’s rule:

First, his insecurity – political, to start with, and psychological. Having fought his way into power, he faced continuing opposition and uncertainty for the early years of his reign. He successfully played off different Roman leaders against each other, and ruthlessly put down internal opposition to his rule. Members of his own family, including his father-in-law and his wife Mariamme (of whom he was very fond, but who had Hasmonean blood in her), fell foul of his suspicions and were killed. He continued to be nervous, and in the latter years of his life he was obsessed about possible threats to his position. Three of his own sons were executed, including his favourite Antipater, just days before Herod’s own death. Herod’s Palestine was a police state, living in fear. The murderous reaction to the announcement of the birth of a ‘king of the Jews’ (Matt. 2:2) is entirely in character.

A second more positive characteristic of Herod’s reign was his achievement as a builder. He built fortresses, palaces, temples and theatres. For example, by the Dead Sea there was Machaerus on the East coast, where John the Baptist was imprisoned and finally executed, and Masada, the magnificent hill-top fortress complex on the west side of the Dead Sea, where the Jews would so heroically resist the Romans in the war of AD 66-70. Herod built the port of Caesarea on the Mediterranean, providing a massive artificial harbour on a coast where there is hardly any natural harbour. This became the key entry/exit point to the country, through which almost everyone would have passed (including the apostle Paul following his arrest, Acts 23:33). Herod did great building work in Samaria, but most famous of all was his work in the Jerusalem area, where he built a whole variety of buildings, including a palace for himself, a theatre, an amphitheatre and a hippodrome, where crowds would come to watch sports and shows.

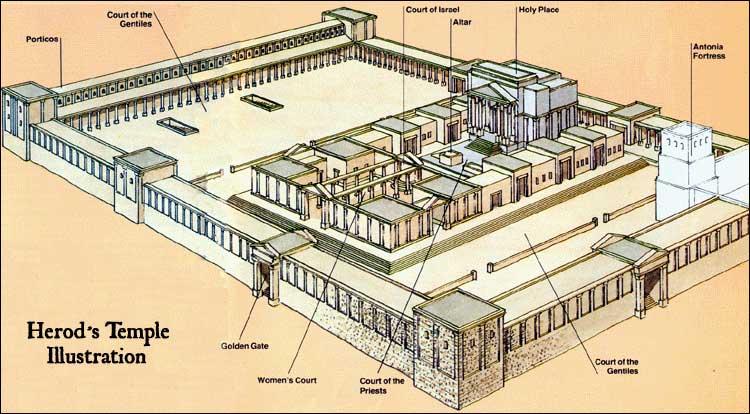

Multimedia Insight

It was, however, his work on the Jerusalem temple that was most striking and is most important for NT studies. This was started around 19 BC. The work on the main part of the temple took about ten years to complete, but the whole work went on until AD 63 – just a few years before it was to be destroyed by the Romans in AD 70. Nehemiah’s temple was a modest affair, not in good repair when Herod came to power. He, however, transformed it into one of the wonders of the ancient world, employing a huge workforce – Josephus speaks of 18,000 being unemployed when the work finally stopped in AD 63. He extended the temple area so as to cover twice the area of the original temple built by Solomon (Herod’s temple was about 500 yards long, 325 yards wide); the central shrine was surrounded by courtyards, colonnades and other surrounding buildings, built and decorated magnificently, with gold and silver and ornamental gateways.

The importance of the temple for a study of the NT is clear. The Jews had very mixed feelings about Herod: he was ruthless, and he taxed them heavily, as he needed to, to pay for his building work and his own lavish lifestyle. He was seen as an outsider (as an Idumean) and not as a proper Jew. Culturally he was more Greek than Jewish, as his building programme showed (it included building temples to the Roman imperial family), in the use of Greek as the court language and in his own lifestyle. However, despite everything, the temple, which he did so much for, was something that inspired admiration and devotion.

Herod died in 4 BC, and in his will left his domain to the three of his sons in whom he still had confidence – he bequeathed Judea and Samaria (including the title ‘king of Judea’) to Archelaus; Galilee and Perea to Antipas; and parts of Northern Transjordan and Gaulinitis (the area of the Golan Heights) to Philip. All three sons headed off to Rome, to gain Roman support; Antipas pressed his claim over against that of Archelaus. A delegation of Jews also went asking that none of the Herodians be appointed king. However, the Roman emperor Augustus eventually confirmed the will, except that he declined to give Archelaus the title of ‘king’.

During the gap between the death of Herod and the establishment of his sons, there were various anti-Roman risings in Jerusalem, in Judea (led by a shepherd Athronges) and in Galilee (led by a man called Judas, who took over the Galilean town of Sepphoris). This revolt led the Roman governor of Syria to march into Palestine with his legions: he destroyed Sepphoris, a new town near Nazareth, and had 2,000 Jews in Jerusalem put to death by crucifixion.

Of the Herod sons, the two who are of most interest from a NT point of view are:

a Archelaus His brutality and his interference in temple affairs (e.g. in deposing two high priests) made him a hated man and, in response to delegations from Judea and Samaria, he was removed from office by the Romans in AD 6 (Matt. 2:22). Direct Roman rule was then being imposed.

b Herod Antipas He was a much more able ruler, who ruled in Galilee until AD 39. He followed his father as a builder, for example building a magnificent city, Tiberias, on the west shore of Lake Galilee. He was more sensitive to Jewish feelings and scruples than others in his family, though he upset the pious Jews by divorcing his wife and marrying Herodias, who had been married to a brother of his. He was denounced among others by John the Baptist, a popular prophet. Herod arrested John, and in due course executed him, at the instigation of Herodias. Herodias

eventually proved the downfall of her husband, when she, with her usual ambition, persuaded Antipas to ask the Romans for the honour and title of king. The Romans suspected his ambitions, and he was rewarded with being deposed from office and sent to exile in France.

Although Jesus’ ministry was mostly in Antipas’s Galilean territory, the Gospels only describe them meeting once, in Jerusalem after Jesus had been arrested (Luke 23:6- 12). Herod had heard plenty about Jesus (e.g. Mark 6:14), but it may be that Jesus deliberately kept out of the way of the man who killed his friend and mentor John the Baptist (cf. Luke 13:31-33). Jesus is never described as visiting the big Greek towns of Sepphoris and Tiberias where Herod’s influence and rule will have been strongest. Jesus, then, was in Antipas’ territory when ministering in Galilee, though villages to the north like Bethsaida and Caesarea Philippi were in Philip’s territory. But when he visited Jerusalem he left Antipas’ jurisdiction.

Judea and Samaria had been under the direct rule of the Romans, in the form of a Roman governor (a ‘prefect’ or ‘procurator’), since the time of Archelaus. Although Archelaus had been much disliked, direct rule was not universally welcomed by the Jews, since it represented the extending of pagan rule over their land. In fact, when it was first introduced in AD 6, there was a major rebellion against a census conducted, for taxation purposes, by Quirinius, the Roman governor of Syria. The census was resented for both financial and theological reasons. The rebellion was led by a Judas from Galilee, but was swiftly crushed.

PONTIUS PILATE

Easily the most famous Roman governor was Pontius Pilate, who was appointed in AD 26. He may have been a protégé of Sejanus, a very powerful figure in the Roman imperial court with anti-Jewish tendencies. Certainly he managed to offend the Jews soon after taking office. For example, breaking with earlier precedent, he ordered the Roman troops who were stationed in Jerusalem to carry their military standards into the city; the Jews were infuriated at what they saw as pagan images entering the holy city. The popular protests eventually forced Pilate to withdraw the order.

In a similar incident Pilate upset people by trying to have some golden shields inscribed with his name and that of the emperor erected in Herod’s palace in Jerusalem. This time the Jews protested to the Roman emperor himself, who told Pilate to move them to Caesarea. Pilate also caused offence by raiding the temple treasury to help pay for an aqueduct into the city. This secular use of sacred funds again led to protests and violence. Pilate’s dealings with Jesus and the Jewish authorities, at the time of Jesus’ arrest, must be seen in the context of (a) Pilate’s previous record of poor relations with the Jews, which will have made his position vulnerable in all sorts of ways; and (b) the general resentment in Palestine against foreign rule. The Gospels refer to ‘an insurrection’ at the time of Jesus, and to ‘bandits (or robbers)’ being crucified with Jesus, who could have been nationalist freedom fighters (Luke 23:25).

Pilate’s governorship came to an end suddenly, following his mishandling of a religious uprising in Samaria. A self-styled prophet, perhaps Messiah, had attracted a crowd to Mount Gerizim. Pilate sent in his troops, who inflicted heavy bloodshed. The result was a strong protest to the senior Roman governor of the area – based in Syria – who ordered Pilate back to Rome. Pilate’s failure to manage the religious affairs of his subjects wisely was finally his downfall.

AFTER PILATE Pilate’s immediate successor, Marullus (AD 37-41), presided over a crisis in AD 39, when the megalomaniac Roman emperor, Gaius Caligula, took offence at the Jews and ordered his statue to be set up in the Jerusalem temple itself. This looked like being another ‘desolating sacrilege’. The Jews were in uproar, and furious efforts were made to stop the order being carried out (including by Agrippa, one of the Herod family, who was a friend of Gaius). The thing that decisively saved the day was the death in Rome of Gaius by assassination.

Marullus was succeeded by Agrippa, the last of the Herods to have power in Jerusalem. He ruled from AD 41 to 44, and was popular with the Jews, living rather piously and also, according to the NT, taking action against the unpopular Christians (Acts 12:1-2).

The following period of rule by Roman governors was turbulent. Fadus (AD 44-46) put down and beheaded a prophet called Theudas, who promised to lead people dry-foot through the Jordan to conquer the promised land. Tiberius Alexander (AD 46- 48) crucified two sons of Judas the Galilean, presumably for nationalist violence. His governorship was marked by a particularly severe period of famine. Cumanus (AD 48- 52) presided over various troubles, including an incident in Jerusalem when a soldier offended Jewish sensitivities, leading to a disturbance in which, according to Josephus, 20,000 people were killed. There were also major tensions between Jews and Samaritans. The governorship of Felix (AD 52-60) saw more unrest in Palestine, with groups of revolutionaries or ‘zealots’ (such as the ‘sicarii’ who specialised in assassination) and religious prophets (including a Jew from Egypt) being active and gaining support. Felix was ruthless in response (Tacitus Hist. 5:9). Albinus (AD 62-64/5) and Florus (AD 64/5-66), whose brutal and rapacious rule triggered rebellion, and the Jewish war. The Jews fought fiercely and hoped for a Maccabean-style deliverance; but it did not come, and the infighting between different groups in Jerusalem did nothing to help. In AD 70 Jerusalem was captured, the temple destroyed and burned down.

JESUS' CONTEXT

The brief sketch that we have presented of the history has brought out various of the ingredients which made up Jesus’ world:

Living under a Pagan Superpower

From the time of the OT right through and into NT times, the Jews of Palestine had been living under the shadow of a powerful pagan superpower. In the NT era Rome was militarily powerful, culturally vibrant, rich and pagan. Although the Romans did not seek to suppress Judaism, still the culture and way of life and infiltrated Palestine, and many of the rich and influential people, notably the Herods, were into the Graeco-Roman way of life. The architecture, the entertainment and other aspects of the foreign rulers were attractive to many. Some of the Jews, for example the high-priestly families and the tax collectors, were doing very well under the Romans, and had a vested interest in the survival of the status quo. On the other hand, some of the Romans and other Gentiles found the religion of the Jews intriguing and their morality attractive.

Rich and Poor

People had been dispossessed to make room for the friends of the governing class, and the gap between rich and poor was wide. Taxation hit most people, often very hard – there were individual taxes, taxes on goods, as well as the traditional temple tax. Tax collectors were unscrupulous and unpopular. Debt was a major problem.

A New Desolating Sacrilege

There was also the fear of what might happen in the future, and of a new ‘desolating sacrilege’. The great fear was that the Romans might become much less benign, and defile things that Jews felt sacred. From time to time things did happen to enflame people’s anxieties. Whereas some of the Roman officials were shrewd and sensitive, some were provocative and even violent. Society was generally violent in a way that some of us can hardly imagine: crucifixions and massacres of people who opposed or offended the rulers were commonplace.

Maintaining The Traditions

In face of the foreign rule, some people became lax about their old religious loyalties. Thus at the time of Antiochus Epiphanes a significant number of Jews were willing to go along with his introduction of Hellenistic culture. There was plenty of glamour and attraction in the Graeco-Roman culture and way of life. But many were spurred on to greater loyalty: in the absence of political freedom, the traditions of Judaism became all the more important as a mark of Jewish identity.

In particular three things became especially sensitive:

- the OT law

- the call to be separate from everything unclean (including the unclean foreigner)

- the temple. These concerns motivated the Pharisees, and also the community at Qumran, though they felt that the temple in Jerusalem had been fatally compromised.

Longing for Change

The OT books, especially the prophetic books, spoke of a day coming when God’s judgement would be removed from the people, when they would be free again, and there would be a new age of prosperity and salvation. The end of the Babylonian exile represented a partial fulfilment of that hope, but the experience since that time of living under the thumb of a variety of pagan superpowers left the Jews longing and praying for a more complete liberation, not least at Passover time when they recalled God’s past deliverance from the superpower of Egypt.

The longing turned into action for some: individual leaders appeared, promising salvation and offering themselves as various sorts of messianic deliverers. People flocked to such people. In the NT itself there is mention of Judas and Theudas, not to mention John the Baptist and Jesus himself (Acts 5:36-37). There were also periodic uprisings against the Romans – people hoped that the Maccabean experience of victory through faith and heroism would be repeated.

Religious Confusion and Division

The situation encouraged a variety of religious responses, some justifying the status quo (at least tacitly), some advocating violent resistance, some maintaining religious purity but not violence, and others claiming that the Messiah or a Messiah had come. There was a level of tolerance within Judaism of different points of view, but a very limited level, and divisions could easily become violent, as they did between Jews and Samaritans. The most successful messianic movement was, of course, the Christian movement, and its very success made it the most divisive movement, threatening all sorts of people: its message of liberation from law and temple threatened the Pharisees and also the powerful temple authorities; its eventual inclusion of Gentiles threatened Jewish national identity.

FURTHER READING

- J. Riches The World of Jesus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- DJG2 articles: ‘Archaeology and Geography’, ‘Herodian Dynasty’, ‘Jerusalem’, ‘Rich and Poor’, ‘Rome’.

- Stambaugh & D. Balch The New Testament in its Social Environment. Louisville: Westminster, 1986.